Descartes and the Church

Faith and Reason in the 17th Century amidst Theological Controversy

In the 17th century, René Descartes (1596-1650) emerged as a pioneering figure, often hailed as the quintessential 'Renaissance man' for his groundbreaking contributions to metaphysics, mathematics, and physics. While his innovative philosophy initially faced significant scepticism from the Church, Descartes remained steadfast in his commitment to his faith and the Church's teachings. Over time, perceptions have evolved, and today, Church documents frequently reference Descartes' philosophy with approval. In this blog post, we will delve into Descartes' complex and often tumultuous relationship with the Church, exploring the nuances of their interactions and the lasting impact of his philosophical legacy.

Descartes’ Early Life and Education

René Descartes was born into a Catholic family and attended the prestigious Jesuit college of La Flèche from 1606 to 1614. A brilliant student, he nonetheless began questioning the relevance of the material he was taught upon leaving college. His legal studies at the University of Poitiers failed to dispel this lingering doubt. Seeking a deeper understanding of the world grounded in his own experiences and observations, Descartes embarked on travels that enriched his mind and sharpened his thinking through conversations with diverse individuals he met. These journeys were not without peril, as they took place during the tumultuous period of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). This conflict, characterised by the geopolitical ambitions of emerging nation-states and ongoing disputes between Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists, brought death and destruction across Europe.

Descartes' Philosophical Breakthrough

In 1637, Descartes presented his innovative approach to philosophy in his book "Discourse on the Method" (Discours de la Méthode). In this seminal work, Descartes advocated for the use of radical doubt as a method to pave the way for the discovery of truth. He posited that one could entertain doubts about everything—from observations and personal existence to the very existence of God. However, through this process of doubt, Descartes argued that a fundamental truth emerges: the undeniable fact of one's own thinking (cogito).

Descartes contended that this unique human capacity for reasoning empowers individuals to construct their philosophical worldviews encompassing God and the world, distinct from theology. He famously articulated this perspective with the phrase 'I think, therefore I am' (cogito ergo sum), asserting that God, the Creator, endowed humans with the capacity for reason and does not deceive us (Deus non fallax).

While the premise of the 'cogito' - God does not deceive us- carries profound theological connotations, Descartes remained unwavering in his conviction regarding the power and autonomy of human reason. Unsurprisingly, this stance sparked controversy within both Catholic and Protestant academic circles. The notion of entertaining doubts about God's existence did not resonate with Christian intellectuals of the time. Furthermore, they objected to any notion — intentional or unintentional — that human reason could evade the consequences of the Fall. While it is true that God does not deceive us, our capacity for reasoning is marred by Original Sin, rendering it imperfect. As a result, Descartes’ opponents argued that human reason alone cannot construct a comprehensive worldview that includes God without the guidance of divine revelation.

Descartes and the Church

In 1973, professor G.A. Lindeboom (Free University of Amsterdam) published an essay on the relationship between Descartes and the Church. The following discussion is based on this study. Lindeboom portrays Descartes as a faithful and practising Catholic, albeit not pious; in fact, he is described as rather 'cold-hearted' (p. 22). Despite his radical views, Descartes maintained a deep appreciation for the education he received from the Jesuits and sought to stay connected to the Catholic intellectual tradition. This is evident from the fact that when he arrived in the Netherlands in October 1628, he brought along only his Bible and a copy of Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologiae.

Descartes came to the Netherlands hoping to ‘find a better climate to think’, or so he claimed. A few months before, Descartes had attended a discussion at the house of the papal nuncio in Paris, where his philosophical interventions made a favourable impression. One of the dignitaries present impressed on Descartes that he should try to renew the philosophical teaching at the universities by offering a modern alternative to the dominant Aristotelianism that was still being taught at the time. In other words, Descartes felt the Church had sent him on an intellectual mission.

Descartes was critical of many positions of the Church but insisted that he was not looking for a conflict. When protestant theologians accused him of atheism, he became so upset that he wrote the Meditations to offer ontological proof for the existence of God within reason. Descartes dedicated the book to the professors and students of the theological faculty of Paris, which then was still the most prestigious theological institution in Europe (p. 35).

After his death, the growing opposition, especially among the Jesuits, to Descartes’ philosophy led in 1663 to the inclusion of his works in the Church’s Index of forbidden books with the addition donec corrigantur (unless corrected) (pp. 56-57). However, his works remained popular with the Oratorians, who promoted them despite the prohibitions.

Descartes' Relationship with Calvinism in the Netherlands

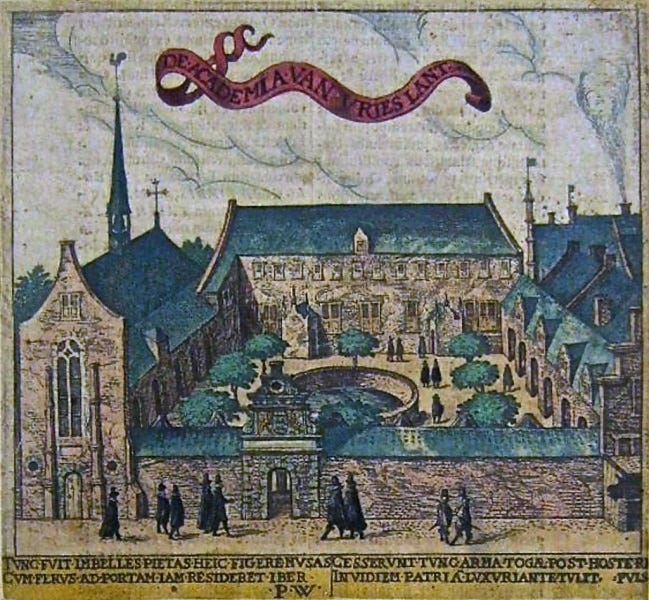

In 1629, Descartes attended lectures at the Calvinist University of Franeker (Academia Franekerensis, 1585-1811). Because his house was separated from the city by a moat, he could arrange for private Masses to be said for himself and his servants throughout his stay (p. 25). Later in life, Descartes claimed that he never attended a Calvinist service, although he once briefly 'stepped in' to listen to a sermon (p. 24). Interestingly, he seemed to have 'forgotten' that his illegitimate daughter was baptised—in his absence—in 1635 in a Calvinist church by his Protestant friend Revius, who had made earnest attempts to convert him to Protestantism (p. 25).

Simultaneously, Calvinist theologians, led by Gijsbertus Voetius (1588-1676), strongly criticised Descartes' work. Their concerns were not unfounded, as Descartes' ideas sparked academic disputes at Protestant universities in Utrecht in 1642 and 1643, as well as in Leiden in 1647 (p. 11). While Voetius denounced the 'new philosophy' from the pulpit, there were plans to bring Descartes before a panel of a Protestant theological faculty or a council of the Reformed church (classis) for judgment. Descartes objected, insisting that only Catholic theologians should evaluate his work. In a letter from 1647, he also questioned how a country that had fiercely resisted the Spanish Inquisition could even contemplate organising its own inquisition (p. 48).

Conclusion: Descartes and the Church today

In 1973, Professor Lindeboom's final assessment of the relationship between Descartes and the Church was far from favourable. In his essay's conclusion, he criticises Descartes for his 'human weakness,' noting that despite facing significant opposition from the Church, Descartes never considered renouncing Catholicism to become Protestant (p. 58). However, in the end, Descartes seems to have been vindicated. He has become a prominent figure in the canon of Catholic philosophy, and many Church documents now contain positive references to Descartes' philosophy as a precursor to the personalistic ontology of the human person in Catholic theology, philosophy, and ethics.

Book: G.A. Lindeboom, Descartes en de Kerk, Kampen: J.H. Kok B.V. (1973).

Picture Descartes: source: wiki commons

Picture University of Franeker: source: wiki commons

Picture Meditationes: source: wiki commons